Mapping Sexual Harassment in Egypt

Women everywhere experience sexual violence in public – from ogling, comments and catcalls, online harassment, touching and stalking, to sexual assault and rape. Sexual harassment in particular is an everyday struggle that Egyptian women have to endure, and in many cases accept, while going about their daily life. It is often seen as a trivial matter with few or no consequences and as the women’s own fault. Not acknowledging the responsibility of perpetrators as well as its impact on women’s perceptions of themselves and their role in society.

Sexual harassment is misunderstood and underreported all over the world. Stigma and shame prevent many women from talking about it or reporting it, and data on the problem is scarce. New web and mobile technologies have, however, opened up possibilities to overcome some of the barriers to documentation and data collection on the issue. HarassMap’s reporting and mapping platform, which has become a key tool for generating data and providing the public with an alternative way to report sexual harassment, has had great success in bringing about debates and discussions about the issue in Egypt and worldwide.

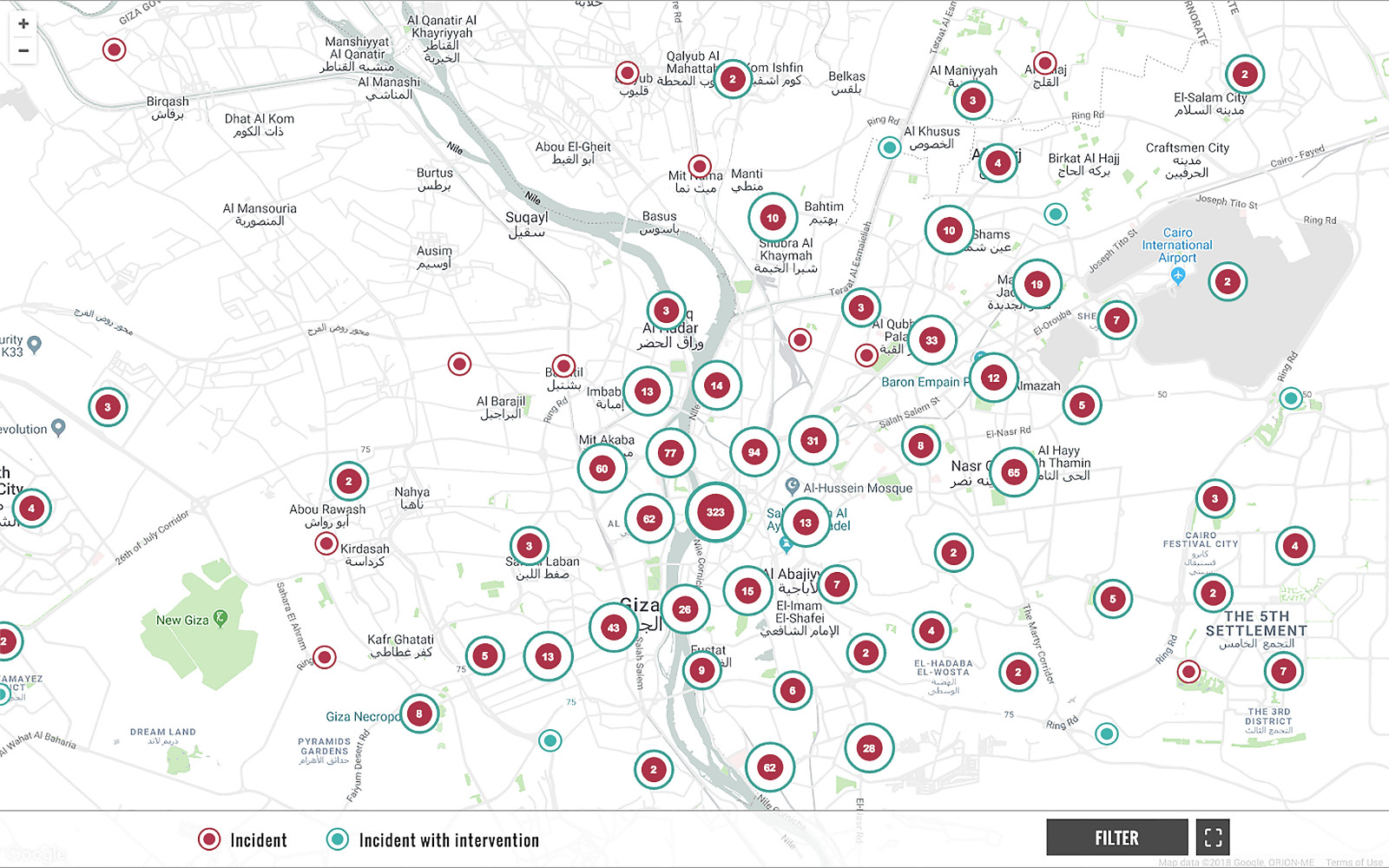

The Map

HarassMap’s map utilizes web and mobile technologies to crowdsource incidents of sexual harassment from all over the country. Individuals who either experience or witness sexual harassment are able to anonymously submit reports directly through the web interface or through Facebook and Twitter, provided that the report includes some basic mapping criteria – including location and date/time of the incident – the reports are automatically mapped using Google Maps and made publically available on the HarassMap website. Each report appears on the map as a red dot that, when clicked, displays the full information of the report in its original language (Arabic or English). Each report includes not only the location and the date/time but also a text description of the incident, the type(s) of sexual harassment (for example comments, stalking or following). Sometimes it also contains additional information on the age or educational level of the reporter and harassed person and whether or not witnesses who intervened are included. Each report receives a response with information on how to access free legal services and psychological counseling.

The data on the map is open for anyone to view and use and serves multiple functions. This includes providing testimony by those who experience or witness sexual harassment as to the seriousness of the problem, serving as data for understanding how sexual harassment is evolving in Egypt, providing HarassMap with information that can be used to tailor communication campaigns and educational programs and serving as a tool to motivate the public to report and stand up against sexual harassment. Immediately after launching the map in 2010, HarassMap received a large number of reports of sexual harassment, and over the years the crowdsourced data has helped to reformulate the discussion on sexual harassment in Egypt. It has also helped to challenge stereotypes and misinformation about the issue.

Sexual Harassment: How Effective Is Crowdsourced Data?

Crowdsourcing has emerged as an exciting new method for data collection yet its efficacy remains poorly understood. In 2014, HarassMap published a study1 that investigated the strengths and weaknesses of crowdsourcing tools, such as its own reporting and mapping platform as a data collection method, comparing it to traditional data collection techniques, such as questionnaires, focus groups and interviews. The study suggests that online reporting and mapping can be an effective alternative for data collection on sensitive issues such as sexual harassment.

The findings show that accounts of sexual harassment reported on a map often provide a much more striking picture of the problem than those derived from in-depth interviews, for example. Map reports are bolder, with individuals providing more information about their experience of sexual harassment than they did during interviews. With regard to language, sexualized words and phrases that might cause discomfort in a face-to-face interview setting with an unknown interviewer are much more prominent in the map data.

Reports received via the map are also fuller and more comprehensive than in the interviews, which may suggest that people are more willing to speak about the issue anonymously online than in person. The map narratives exhibit a recurring four-part structure characterized by 1. a set-up of the scene, 2. details of the sexual harassment itself, 3. the response of the harassed individual, and 4. the moral (offering public comments on sexual harassment in Egypt in general). This structure was not seen in the in-depth interviews, in which shorter question and answer exchanges were more common than extended narratives. What’s more, while “milder” types of sexual harassment, such as catcalls and ogling, were the most common forms of harassment discussed during in-depth interviews, touching, physical assault and rape were the most commonly reported types in map reports. This may represent a major advantage of the map over traditional methods, as it offers a space in which individuals can speak relatively freely and without judgment – making people more willing to discuss sensitive issues and painful experiences, such as sexual harassment or assault. HarassMap is based on the idea that if more people start taking action when sexual harassment happens in their presence, we can end this epidemic.

Link

References

Fahmy, A., Abdekmonem, A., Hamdy, E. & Badr, A. 2014. Towards a Safer City – Sexual Harassment in Greater Cairo: Effectiveness of Crowdsourced Data. harassmap.org/storage/app/media/uploaded-files/Towards-A-Safer-City_executive-summary_EN.pdf, 5 June 2017.

Illustrations

Idea of Map: Rebecca Chiao, co-founders and volunteers.

Design an Illustration of Map: Piero Zagami and Noora Flinkman.

Content of map: Anonymous Reporters