A Civic Mapping Project in an Indian Megacity

The Uses and Challenges of Spatial Data for Critical Research

Hyderabad Urban Lab (HUL) looks at cities as a complex set of relationships consisting of relations of production, social relations and relations between citizens and governments. HUL began in mid-2012 with the aim of conducting research on urban issues in a way that would bridge the gap between academic urban research and life at the grassroots. Since the beginning, HUL has experimented with cartography and connected this to both research and pedagogy. HUL makes maps but also advocates to both the government and citizens for a richer cartographic engagement within the city. Over the years HUL has held mapping workshops with a variety of stakeholders and even schoolchildren.

Occurrences in cities are the result of numerous relationships coming together at multiple scales of space and time. As Dennis Wood (2010) says, one can portray these intersections by bringing things together on a common level. It is this level and the propositions that make the map. As Peter Turchi (2004) puts it, maps are no different from literature in the sense that they attempt to explain human realities. It is the cartographer’s privilege to select what is included and what isn’t. Thus maps in general are assertions of the state of the world which cartographers desire. This is why maps are tools of power. The state, which in many countries holds exclusive rights over mapping, can choose to portray certain versions of reality while omitting others. Corporations with large amounts of spatial data also hold great power over the way the world is increasingly being perceived and

experienced through digital maps. In this context, practices of critical mapping stand outside the norm of using maps to declare sovereign power or to facilitate consumption. They, in fact, talk back to this power and help citizens or communities to represent their own geographies.

Since its inception, HUL has used critical mapping as a core methodology in research, a key tool in engaging with various urban stakeholders and also as an essential component of its pedagogic outreach. Having undertaken a wide variety of mapping projects and teaching workshops, our practice itself has deepened rigorously. Here we present, with examples from our work, four of our key mapping practices, the principles that direct them, the practical difficulties we face and the reasons why we are committed to working with open data and crowd-sourcing.

Community Mapping

Maps of Bholakpur’s Scrap Markets

HUL’s earliest project was to build a digital tool in order to enable collaborative research with the community in a historic neighbourhood called Bholakpur – a former hub of leather tanneries and today a hub of scrap markets. The motivation was to understand the political economy of the markets and also to revalorize the neighbourhood in terms of its dynamics and economic productivity, something the government has been neglecting.

Members of the community responded eagerly and played a major role in facilitating the process. They helped us to collect GPS tracks and to identify the key objects represented on the map. The community members quickly understood the usefulness of the map and also that they had taken ownership of it. The idea that community mapping might be an empowering process was affirmed by maps drawn to contest the government’s view of Bholakpur.

Taking ownership of these maps also enables the community to make claims on their own knowledge of the place. Bholakpur’s scrap markets have been facing pressure from the government and are threatened with eviction. This pressure is a result of popular perceptions regarding persistent water contamination in the area and its connection to the presence of the scrap market. With the help of maps, local field workers are able to identify specific locations in the neighbourhood in which contamination is persistent. This data can then be collated with the locations of scrap processing units and their runoff. The spatial data was able to demonstrate that there was little or no correlation between water contamination and the presence of scrap markets. An ability to work with maps and spatial data has given residents of the neighbourhood leverage in negotiating with governments and NGOs that work in the area.

Crowd-Sourcing Data – Bus Frequency Map

The Andhra Pradesh Road Transport Corporation (APSRTC) runs most of the city buses in Hyderabad but does not have a public database of all bus routes and time schedules in the city. After extensive cleaning of a rather faulty list of bus stops and bus routes acquired from the APSRTC, the result was the first geospatial database of bus routes in Hyderabad.

The map generated from this database is useful for citizens but it also helps us to understand areas in the city that are deprived of public transportation. With this base map, we asked: How do people travel in areas with no public transportation available? We presumed that the answer was represented in shared auto rickshaws. As an experiment, we put out a public call for people to contribute shared auto rickshaw routes that they knew of. Within 8 hours, we had details on 85 routes in the city. Adding all of these routes to the existing frequency network map further enhanced the public database on mobility in Hyderabad.

Public Audits Using Maps – Map of Public Toilets

Public audits and fact-finding missions have long been a useful methodology employed by activist groups and other civil society organisations in India for holding the government accountable for the rights of citizens. We believe that the addition of maps as a tool will be invaluable to this methodology.

The current government of India announced that sanitation would be one of its priorities. While the government was targeting the people’s attitude towards defecation in public, we published our map in order to put these attitudes in the context of the available infrastructure. Hyderabad, a city of more than 6 million people, has only 186 public toilets. Our map highlights the unjust and sparse distribution of toilets in the city. Another focus of our dynamic map is to show the inequality between available toilet facilities for men and women. The data was collected through a public audit conducted by the HUL team and some volunteers.

Our map also illustrates the perverse outcome of an incentive for free advertising on the outer walls of toilets provided to private contractors if they built new public toilets. As a result, 50 new toilets were constructed. However, many of them were located in squares which were already served by a public toilet; sometimes they were built just adjacent to old ones while leaving many areas of the city still unserved. Perplexed by this choice of location, we supplemented our mapping exercise with an audit of some of these toilets. We found that the incentive structure meant that private contractors built toilets where their visibility as billboards would be greatest. Although the incentive had been offered with good intentions, poor monitoring of the outcomes resulted in inadequate, sometimes redundant results with respect to the goal of expanding access to public toilets. Many of our mapping exercises are conducted in this audit modality with which we hope to be able to persuade the government to plan public amenities and implement policies with greater care.

Cleaning up Public Data

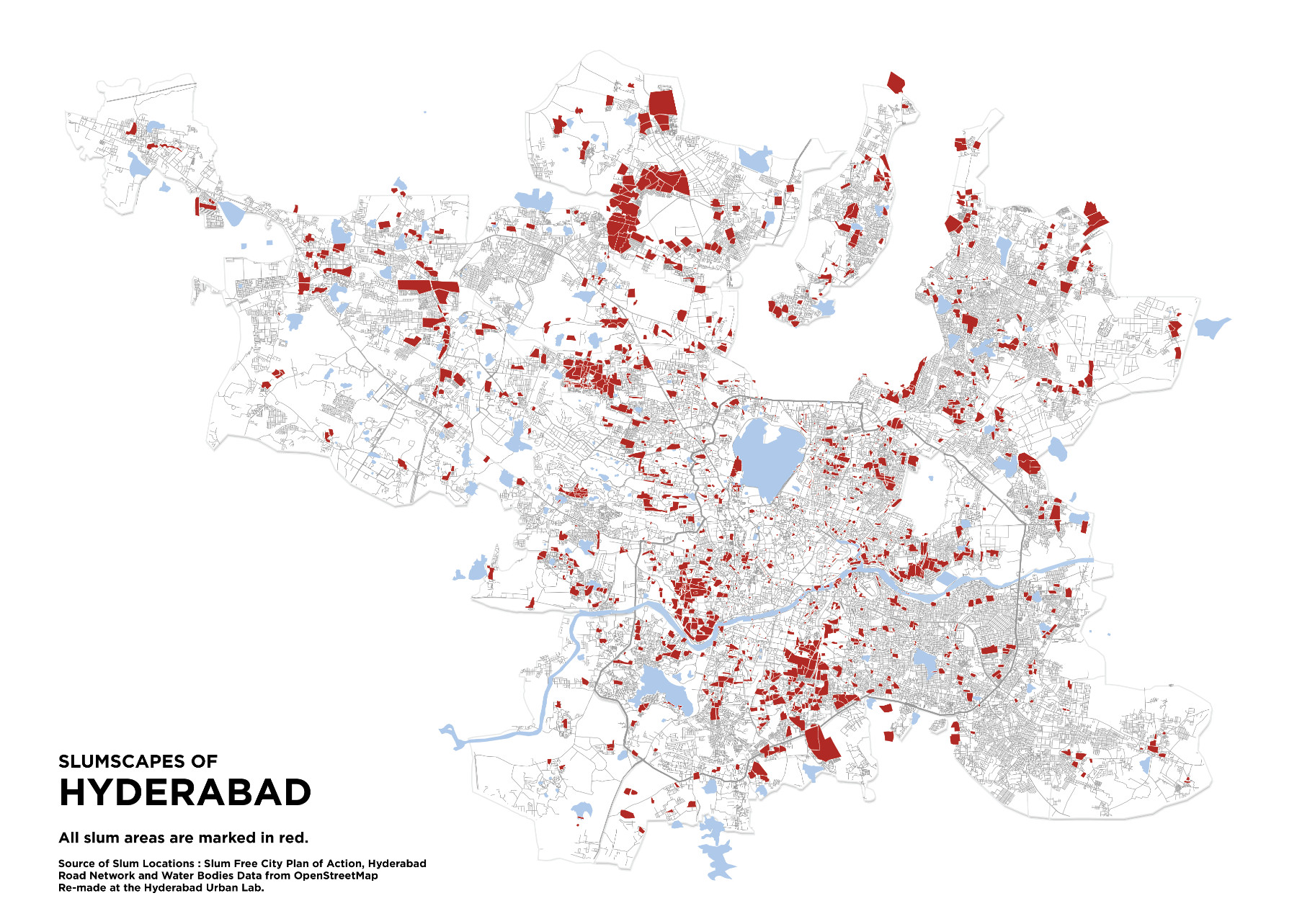

Atlas of Slums in Hyderabad

Most cities in the developing world such as Hyderabad tend to have data in closed and archaic formats which impede interoperability. They also lack inventories to keep stock of multiple data sets across space and time (e.g. it is hard to find any data on pre1990 municipal wards for Hyderabad). The periodic realignment of administrative boundaries and enumeration blocks makes it especially hard to build cohesive data sets over time. Uncertainty about data rights is another major problem. These issues often represent obstacles for anyone interested in doing research in these cities.

In a bid to transform Hyderabad into a “slum-free city” (real worldclass city), the city government was going to conduct a count of all the slums in its jurisdiction, which amounted to 1476. As is common, this task was outsourced to a private company. Unbelievably, the task was conducted within 30 days and with a budget of just 1.8 million rupees (roughly 23,000 Euros). We highly question the validity of this information and the legitimacy of how the data was collected. In any case, some data was produced. Although there are some glaring inconsistencies, the map gives us the only available representation of slums in Hyderabad, and, more importantly, this is a representation of how the government itself sees the “slumscapes” of the city.

An atlas of maps depicting various characteristics of recognised slums in Hyderabad was put together through a painstaking process of cleaning this inconsistent data. By sharing these maps with the government, we wish to inform it about the possibilities for analysis and planning offered by clean spatial data. Through regular articles and interventions at consultation meetings, we are trying to push the government towards improving their data practices. This is a long-term project because we believe that apart from civic mapping projects, public data itself should be publically accessible in general.

Conclusion

Being in the open domain, our maps have constantly elicited new questions and new proposals from the citizens looking at them. It is evident that the general ethos to support the fruitful use of open data as well as the employment of crowd-sourcing practices is already happening in our city. With each new project, we try to tap into that ethos. With each workshop, we try to further encourage it. With each engagement, we try to extend the conviction that planning cities can be a more democratic exercise.

References

Turchi, P. 2004. Maps of the Imagination:The Writer as Cartographer. San Antonio,Texas:Trinity University Press.

Wood, D. 2010. Rethinking the Power of Maps. New York:The Guilford Press./p>