Property matters

Mapping housing ownership in Switzerland

A disturbing silence

Knowledge is power and the power to conceal property relations in housing is widely practiced in Switzerland, despite laws supposedly guaranteeing transparency. The housing sector and its attached real-estate industry cement inequalities and present a well-hidden secret in plain sight. Real Estate is the place to sink the “gold” of overburdening wealth for some – private investors, banks, real estate companies, pension funds – while, the buildings of bricks, wood, and concrete are home to others – ordinary people, and urban citizens. To unveil mechanisms that turn peoples’ homes into a place for investors to amass their richesse, while pushing more and more people towards housing insecurity is the goal of our poster series Betongold. Betongold literally means concrete gold and aims to describe how houses are turned into investment opportunities, what critical geographer David Harvey famously called the spatial fix of capital.

The story of the Betongold series dates back to 2016. At that time, a new wave of mass cancellation of rental contracts and destruction of houses swept through the city of Basel. Located on the banks of the Upper Rhine, Basel is Switzerland’s third-largest city, directly bordering Germany and France. Undergoing a transition from a former industrial city to a service-focused urban site, in recent decades, Basel has been boasting as an international cultural capital hosting the world’s biggest Art fare (Art Basel), promoting itself as a comfortable place to live for highly skilled expats working at some of the biggest pharmaceuticals worldwide (mainly Novartis and Roche). In the mid 2010s this transition began to reflect in successive waves of mass displacements of long-term renters.

In reaction, a movement for a right to the city and a right to housing began to form in Basel, including affected residents from the Steinengraben Street, activists running a lunch table in an occupied kiosk at Schanze, tenants endangered with eviction at Mattenstrasse and a group of pensioners expulsed from their homes by their own pension fund at Mülhauserstrasse. At this point, it became clear how little is known about real estate ownership in our city. Who were the owners of the buildings that tenants had to move out from? What was the underlying logic driving mass cancellation of rent contracts? What happens to housing security, when investors’ financial interests dominate? Our conversations and research quickly led us to look at housing ownership and the need to learn more about shifting property relations in the so-called real estate industry. Until today – almost ten years later – most debates about the housing crisis are marked by an uncomfortable silence about the actors involved.

Stadt für Alle and the power of forming critical collectives

The poster series Betongold emerged out of years of research and activism. Two intertwining threads of organization – a right-to-the-city movement and a group of activist researchers – led us to establish our independent association: Stadt für Alle Basel (City for all). The right-to-the-city group in Basel started in 2016 on a Wednesday night at a collectively run bar. Nils Boeing – a long-term housing activist from Hamburg – delivered an inspiring talk sharing experiences from Hamburg’s right-to-the-city movement, when a group of Basel residents decided to get together. In a lose format, we began to meet weekly, reading theory and learning from urban struggles past and present. Reading and discussing led to action – overcoming the isolation of atomized individual houses fighting for their right to stay. During dozens of meetings, we started producing flyers, posters, stickers, a manifesto and a brochure about the right to the city in Basel. We also mobilized for protests and organized public actions including the temporary occupation of the Marktplatz square in the city center. These interventions created a tight-knight community and eventually led to the establishment of a monthly gathering to bring together tenants struggling to keep their homes. The Häusertreff (literally meaning houses’ meeting) was born. Every second Wednesday of the month, we gathered in this meeting open to everyone to discuss and get support for their struggles against cancellations, as well as to plan and prepare solidarity interventions. The project developed quickly and trust amongst people, houses, and projects began to grow.

Almost simultaneously, a second project evolved. A group following one of the key housing struggles of Basel in 2017 – the fight against the displacement of pensioners by their own pension fund at Mülhauserstrasse 26 – decided to examine more closely the role of pension funds in gentrification. They found that pension funds had become a key player in the real estate sector, while simultaneously being an integral part of the Swiss social security system. The privatized system of pension funds was originally conceived as part of the reform of the Swiss pension system in 1972. It was established in the wake of the neoliberal reforms of the 1980s, and employees have been obliged by law to pay into it ever since. The contradiction became obvious in the 2010s, when pension funds increasingly turned away from stock markets to invest onto more profitable real estate. This shift of “assets” led pension funds to upgrade their existing building stocks in order to increase rents and in some instances – such as Mülhauserstrasse 26 – to displace their own pensioners from their homes. Rental contracts were terminated on a mass scale. The growing frustration with housing accessibility and the mobilization for the right to housing was expressed in the successful popular cantonal vote in 2018, demanding to integrate the right to housing into the constitution of the Basel-Stadt canton, as well as to improve tenants’ protections.

Taking this contradiction of financialized capitalism as a starting point, the group started gathering detailed research on housing property, building a database to structure their findings. At the same time, the group produced a one-time newspaper called Betongold, which discussed in depth the impacts of pension funds’ investments on accessible housing. The newspaper was printed with 60,000 copies, which were distributed for free to every household in the city. This is where the roots of the poster series were layed. In 2018 the two groups and their approaches came together, to discuss what we could do with our work on housing struggles and our research into the property market. Having gathered all this data and built all these networks, we asked ourselves: what next?

A poster series: Betongold!

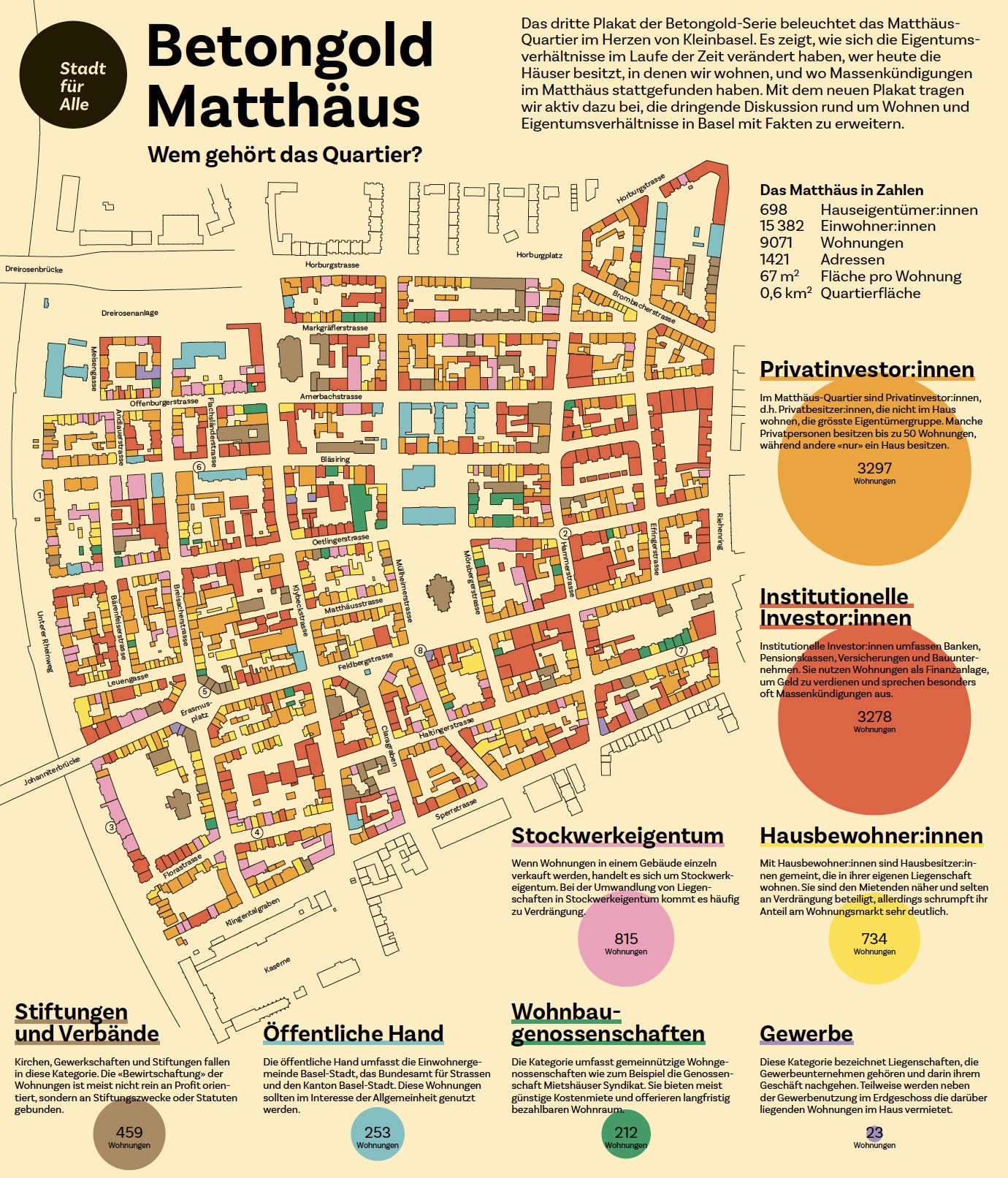

The Betongold poster began as an experiment. We decided to map the ownership of each and every house in Basel’s Rosental neighborhood, an area, where a former industrial zone was being transformed into a residential housing complex, side by side with the autonomous housing project of Mattenstrasse. The residents of this project had played a pivotal role in establishing our right-to-the-city movement. Next, we created a second poster, examining the neighborhoods of Klybeck and Kleinhüningen, an area of relatively low income and in which every second resident is denied voting rights because they are not Swiss citizens. Another major brownfield development in the former harbor area had induced early gentrification here, with real estate investors speculating on rising land prices. In 2024, we completed the third poster project on the neighborhood of Matthäus, which is one of the most densely populated neighborhoods of Switzerland, hosting small shops, bars, coffeeshops, and handcraft enterprises in some of the backyards. Matthäus is a hip area that has seen various waves of gentrification while still being a central site for alternative culture in the city. Most of these neighborhoods mapped, have a significant migrant population, making up almost half its residents. The same applies to our current mapping of Gundeli, the former working-class neighbourhood located ‘behind’ the central station, in 2025.

The realization of each poster project has been an intensive collective process. Four discrete steps made up each of these processes. First, we needed to systematically collect data about housing ownership; second, we categorized types of ownership; third, we visualized our findings in an accessible format; and fourth, we sought for ways to share our work widely with the affected residents in the respective neighborhoods. Each of these steps had its own perks.

How can you find out who owns your house? This is a difficult question for tenants to answer, especially when their main point of contact is not the owner, but a housing management firm, as is the case in most of Switzerland. However, in the canton of Basel-Stadt laws and regulations guarantee the public accessibility of housing ownership data. The cadaster office (Grundbuchamt) is responsible for publishing the information. Practically, up to 20 properties can be examined on a website per day and person – a small number given that there are approximately 19,000 properties within the municipality´s boundaries. When we began collecting this data, we literally started out at zero. Today, in 2025, we completed the collection for all properties in Basel. However, with a federal system, every canton and municipality has slightly different laws and regulations governing the public accessibility of houseownership data. In 2025, we are also going to expand our approach of data collection by expanding it to other municipalities such as Bern, Lausanne, Luzern, Zürich or Winterthur.

In the second step of the poster project, we transferred the ownership data to our custom-build database and added critical information. Thanks to the incredible persistence of our database collector-in-chief, a pensioner with unmatched dedication, we began categorizing housing ownership after organizing collective data-gathering workshops. Whether a property is owned by private individuals, pension funds and insurances, housing cooperatives, the state, or service and industry companies, each property was labelled in specific categories. These categories serve two functions: Firstly, they allow to organize overwhelming details, and secondly, they protect individual rights to privacy.

In a third step, we discussed how to present our information in a readable and visually appealing format. We decided on a poster format, that can be folded into a neat small A5-leaflet. This would include colorful maps and visualized statistics, for example about the ten biggest housing owners in the neighborhood and historical changes in housing ownership since the 1960s. Hence, each poster would look different, and we benefited every time from the input of a different designer who worked or lived in the respective neighborhood.

The fourth and final step was the dissemination. As a grassroots initiative, our association Stadt für Alle has always sought to democratize debates about urban transformations. By making evidence publicly available, we show with facts that displacement and changes in property relations are not isolated incidents, but significant shifts in property ownership from individuals to institutional investors are reflected in the data. Our target audience was not just urban elites in planning departments or at universities, but literally every resident living in the neighborhoods that the posters focused on. We printed 4,000 to 8,500 copies of each poster and, in a collective action, distributed them to every single postbox in the neighborhood, hoping that people would read them or even hang them on their kitchen or bathroom doors, as they often do. The free dissemination of the printed posters included invitations to public discussion rounds. Debates on how changing property relations affect the places we live in were further elaborated on during urban walking tours, or courses at the University of Basel.

Let’s talk about housing financialization

Although each of the posters shows striking differences, they all have one thing in common: a powerful shift of real estate properties is becoming visible. Financialization of housing means institutionalized investors (collecting stock market money, state-funded pensions, or investors´wealth) are buying up development sites and existing housing blocks on a massive scale, while small private landlords who live in and their own homes are becoming a rare phenomenon. This transformation of houses into assets for speculation fundamentally changes neighborhoods. The use value of a home as a lived space becomes secondary. In a financialized logic of real estate markets, the potential profit from homes becomes the primary driving force. While the result remains the same, the tactics may differ once profit is established as the primary goal of an apartment. Renters face increasing rents and/or displacement. Be it by buying-low and selling-high strategies; disinvestment by cutting maintenance costs; luxury renovations to raise rental income; or mass cancellation of rental contracts to allow new renters to be charged premium prices. Once rental prices start to increase in a neighborhood, there is an incentive to convert formerly affordable housing into profitable apartments. The slow expulsion of economically disadvantaged people as well as rapid gentrification through mass cancellations of rental contracts is destroying tenants’ homes. In the case of Basel, these tenants make up over 80% of the entire population. The result is that people lose their homes, institutional investors raise their profits, and most renters struggle to keep up with rising housing costs.

Institutional investors, who often have little connection to or knowledge of a place, have doubled, tripled and quadrupled their share of housing ownership in the neighborhoods. They bought land and buildings on a massive scale over the past decades as the diagram from the Klybeck neighborhood illustrates. At the same time, we find that buildings owned and occupied by private landlords has shrunk significantly, often by more than 75%. These are fundamental shifts in the structure of housing ownership that continue to increase the risk of people losing or being priced out of their homes. This shift in property relations has significant consequences. For example, 83% of all mass cancellations of rental contracts in the past ten years – meaning people were forced out of their homes – were conducted by institutional investors in the neighborhood of Matthäus. By contrast to this, we came across hardly any case, where a private owner living in the house, a housing cooperative or the state were directly involved in the mass cancellations of rental contracts.

Our posters clearly show how houses are being turned into financial assets and treated as objects of speculation, hardly different than investing in any other asset class such as stocks or bonds. And this is happening despite the local specificities of each neighborhood. When inhabitants as renters are abstracted, when numbers and calculations reign, and when contact between a renter and landlord is mediated by professionalized agencies, houses as homes are in danger. The so-called financialization of housing – whereby homes become assets – is operating at full speed in Basel as our posters show. It was only when we started to organize collectively that we realized it was not just unfortunate individual cases of rising rents and rental contract cancellations that were driving us out of our homes. Instead, it is a fundamental economic shift that is changing the neighborhoods we live in. At the heart of this shift are new property relations and ownership structures commanded by financialised logics rather than the needs or visions of residents.

Bottom-up knowledge production for a right to housing

Can a few colorful posters stuffed into postboxes change urban politics? The jury is still out, but after almost a decade of campaigning for the right to the city and the right to housing, we have learnt a lot about the strengths and weaknesses of bottom-up city development. It takes time and a lot of personal resources. Members of our association have gone through various crises and until today we struggle to achieve better representation of the city´s diverse population. After all, the group is still exclusively white, and it took years to achieve a more even gender balance. Finding money to finance the printing, paying external designers and a minimum salary for coordinating the association and the poster process is still challenging, despite living in a city as rich as Basel. However, we have insisted on our independence and shown a certain selectivity when addressing foundations for funding.

On the other hand, the posters should be seen for what they are: the final product of a long and intense process of collaborative knowledge creation within a non-hierarchical structure built on voluntary engagement. By now, the posters have begun to take on a life of their own. They circulate in unknown spaces and are discussed at conferences in Bonn and Frankfurt. They are presented to housing activists in New York and hang in kitchens in Basel and offices in Zürich. They serve as a reminder that any understanding of the housing crisis must address the issue of what primarily organizes housing – the real estate market, whose foundations lie in private property laws that are strictly enforced, mostly benefiting a few while often harming the many. Concrete Gold, where the wealth is invested and new riches amassed from our monthly rents, is a key driver of urban inequality. While the project Betongold alone cannot challenge the mechanisms driving the financialization of housing, we hope that a process of collective, bottom-up knowledge production can work as relevant intervention. By creating an attractive presentation, we aim to deconstruct the statistics and silence surrounding the opaque real estate market. We also provide facts that illustrate that, despite fake news, there is evidence. Institutional investors in Basel are ready to continue buying up homes and cancelling affordable rental prices, as long as real estate remains a profitable business rather than a tool to satisfy peoples’ needs for homes.

Endnotes

Fields, Desiree. “Unwilling Subjects of Financialization.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41, no. 4 (2017): 588–603.

Harvey, David. “Globalization and the ‘Spatial FIx.’” Geographische Revue 2 (2001): 23–30.

Lefebvre, Henri. “Right to the City.” In Writings on Cities, translated by Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas, 63–184. Cambridge, Mass, USA: Blackwell Publishers, 1996.