This Land is Your Land

Strategies for Making the Potential Commons Visible and Actionable

Identifying Objects to Be Considered

To shape the dreams and demands of people living in cities yearning for collaborative creative spaces in which to fulfill the needs of their communities, we start by mapping government-owned land and buildings. Our maps1 show the abundant potential of our shared spaces hiding in plain sight, aching for collaborative management and care. We then connect those maps with tools and strategies understandable to residents of the places we have drawn. We put up signs, we answer the phone, we provide scripts, examples and a community of collaboration. The maps are the starting place for the emergence of true commons to replace warehoused public real estate assets.

There are approximately 660 acres of vacant public land in New York City, distributed across 1,800 vacant lots (596 Acres, 2016). These lots could be gardens, play spaces and sites of community gathering and cultural activity. Located primarily in low-income communities of color, these potential public spaces sit vacant, locked and forgotten, abscesses in the very neighborhoods that most need healthy resources. These gaps only compound a history of redlining, urban renewal clearance and municipal neglect.

As New York City’s community land access program, 596 Acres helps neighbors organize around and gain access to the city’s vacant land. We combine sophisticated online tools and grassroots outreach to turn municipal data into information useful to the public, help neighbors navigate city politics and connect neighborhood organizers to one another through social networking and in-person collaboration. The 596 Acres model is driven by a belief in data-driven, inclusive and democratic local power that is scalable to citywide and statewide issues around environmental justice and public space. In the last four years, through the information we have provided and our direct support, residents have replaced 36 vacant lots with vibrant community spaces.

Mapping What Is Already Ours

The 596 Acres team started in 2011 by hunting down the available information about vacant city-owned land in New York City. We first had to rely on access to City data that was behind a paywall blocking it off from general public access via an academic center at a local college. Realizing that crucial information was being kept from the communities that needed it most, in 2012 we collaborated with other advocates to successfully pressure the City to release the data for free. We also comb the NYC Open Data portal and other city agency and non-profit organizations’ records for information relevant to government-owned property in New York City.

We translate the data into information describing the world as New Yorkers actually experience it, beginning with the very definition of a “vacant” property. The NYC Department of City Planning lumps community gardens, slivers of lots between buildings, and actual publically-accessible vacant lots together under the same VACANT code. After using an automated script, a staff person looking at online records of each property and a survey of community gardens done by gardeners to untangle this, we are certain that our online map shows public land that is actually vacant lots a regular person would understand as being vacant: fenced, full of garbage and weeds and stray cats and discarded weapons (596 Acres, 2016).

The map goes a step further to connect these neglected spaces with the decisions that led to their present state and the decision-makers that have some power to change their future. Some of the decisions were made through a process of “urban renewal”2 in the last century. Understanding that the urban renewal plans weigh heavily on what we see in our neighborhoods today but not being able to find data describing the plans in machine-readable form, we used New York State’s Freedom of Information Law to request decades of planning documents that we read and then translated into data tables we can map and connect with particular properties.

Open Data Becomes Open Space

The key to our success in transforming open data into community-managed open space is that we put information on the fences that surround vacant lots. The online map allows us to figure out what information to put on signs. Our signs announce clearly that the land is public and that neighbors, together, can work towards permission to transform the lot into a garden, park or farm. Both the online map and in-place signs list the city’s parcel identifier, which agency has control over that property and information about the individual property manager handling the parcel for the agency.

Each group of residents must navigate a unique bureaucratic maze: applying for approval from the local Community Board, winning endorsement from local elected officials, and negotiating with whichever agency holds title to the land. The signs and the online map both connect organizers to the staff of 596 Acres, who steer and support residents through organizing support, legal advice and technical assistance.

We work with each unique situation to figure out what is possible and then help people achieve it: Often campaigns end in a permanent transfer to the NYC Parks Department, but sometimes a temporary space for a few years, until other planned development moves forward, is the only achievable outcome.

596 Acres acts in a supporting and advocacy role during each campaign but ultimately each space is managed autonomously, transformed and maintained by volunteer neighbors and local community partners as spaces to gather, grow food and play. Each one gives people an opportunity to shape the city, practice civic participation and self-government, and become co-creators with their fellow New Yorkers.

596 Acres facilitates neighbors building political power by connecting with one another. We do not remain abstracted on the internet or limited by only having face-to-face meetings. By bridging modalities, we have the ability to connect New Yorkers with different strengths and who represent different groups. Online, people can sign up to organize a particular local lot, and then receive updates when others sign up or post. The online tool helps neighbors connect even before getting access to an actual place to build together. However, not everybody we work with ever sees the online tool; many interact in person or over the phone with our staff and simply give us permission to add their information so others can find them.

Data in Action

While New York City politicians rhetorically prioritize urban agriculture and public space, 596 Acres actually fills the gap between place and the people in our neighborhoods. 596 Acres sees – and teaches others to see – empty spaces as sites of opportunity, both for potential green spaces in neighborhoods that lack them, and as focal points for community organizing and civic engagement.

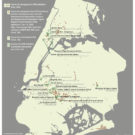

In January 2015, when the City published a list of 181 “hard-to-develop” properties they were willing to sell for $1 to housing developers to build pretty expensive housing, we analyzed the list and found out that it included 18 community gardens, six of which had formed through our support. We published a map and called the impacted gardeners, tapping into and expanding our network, while arming the impacted residents with the tools to advocate for the preservation of the existing community spaces (see map at the end of the article).

Within three weeks, over 150 New Yorkers, including four City Council members, rallied on the steps of City Hall (Tortorello, 2015). A year-long campaign followed. It included Community Planning Boards, City Council and advocates in every level of the administration. On 30 December 2015 the NYC Departments of Parks and Housing Preservation and Development agreed to permanently preserve fifteen of the gardens on the for-sale list; community pressure was so great that the announcement extended to community spaces that were not even on-offer to developers in January: In total, 36 community spaces were permanently preserved as a result of information-driven advocacy – the fourth wave of major garden preservation successes in NYC history.

80 Counter-Cartographies as a Tool for Action

Beyond NYC’s Vacant Lots

Bridging disposition strategies for public resources and the cooperative projects that emerge when these strategies result in community access to land interrupts the narrative of scarcity that permeates all conceptions of real estate and allows neighbors to collectively shape their cities. Strategies derived from the success of 596 Acres have emerged in nearly a dozen cities worldwide, including Los Angeles, Montreal and Melbourne (596 Acres, 2016). In Philadelphia the local incarnation, groundedinphilly.org, was a necessary precondition for the recognition of land stewards and urban agriculture practitioners as an existing constituency whose needs must be considered as that city creates a new protocol for the disposition of public land. Making the potential of abundant vacant public land visible, beginning with mapping, gets the most impacted people into the center of decision-making about our shared resources, inspiring tangible grassroots change well beyond the boundaries of neighborhood vacant lots.

The “Right to the City”, as first articulated by Henri Lefebvre in 1968, recognizes the urban environment as a work of art constantly being made anew by its inhabitants, a space of encounter that allows differences to flourish and generates the contemporary conditions for creative human communities. The right to the city is the right to influence the urban environment that will, inevitably, shape those that spend their days in it. It is really a right to personal autonomy and community self-determination. Our maps are the gateway to the collective, creative acts that shape urban places. They make expressing the right to the city possible for everyday people.

References

596 Acres. Living Lots NYC. livinglotsnyc.org, 4 February 2016.

596 Acres. Other Cities Copy. 596acres.org/about/other-cities-copy, 14 January 2018.

Institute for Applied Autonomy 2008.Tactical Cartographies. In Mogel, L. & Bhagat, A., eds. An Atlas of Radical Cartography. Journal of Aesthetics & Protest Press: 29-37. cril.mitotedigital.org/node/352, 14 January 2018.

Lefebvre, H. 1996. Writings on Cities. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Tortorello, M. 2015. In Community Gardens, a New Weed? nytimes. com/2015/02/12/garden/in-community-gardens-a-new-weed.html, 14 January 2018.

Footnotes

- “Maps don’t merely represent space, they shape arguments; they set discursive boundaries and identify objects to be considered.” (Institute for Applied Autonomy, 2008)

- In 1949 the United States Congress started a federal urban redevel- opment program, or “urban renewal,“ which provided resources to municipal “blight clearance.“ Federal money was made available to local redevelopment authorities to buy and clear so-called “blighted“ areas and then sell that land to private developers.The program followed federal redlining – which distributed access to loans for homeowners along explicitly racial lines – by a decade and was deployed in nearly the same neighborhoods as the ones that had been declared too integrated for safe investment in the housing stock. Urban renewal faciliated the clearance of neighborhoods in which people of different races lived side by side in American Cities between the World Wars.